This Ukrainian WWII saga opens with a tracking shot through the 1942 equivalent of a Bosch painting: for almost four minutes, Sergei Loznitsa‘s camera prowls after three Nazi-arrested locals as they’re led through an occupied Belorussian village, past children and weeping babushkas and relaxing Germans, to the gallows. After that, we’re at the door of a farmhouse, where a steely local resistance fighter comes to execute his erstwhile friend. We only find out why deeper into the film: the farmer was the fourth prisoner to be hung, but he was freed for reasons unknown, a condition that automatically convicts him as a collaborator. The subsequent odyssey through the Eastern Front wilderness proceeds into As I Lay Dying terrain, and Loznitsa makes sure the physical trial stays close to the ground and leave bruises, using long takes, hardbitten hyperreal imagery, and, reportedly, only 72 cuts. In The Fog has the inevitability of an avalanche.

Category Archives: Memorial Day

Like Veterans Day, this emotionally charged commemoration of the American war dead can spark contention along political lines. Again, honor the difficulty and suffering of war; honor the martyr to it.

The Messenger (2009)

Oscar-nominated if under-seen since, Oren Moverman‘s post-Bush drama The Messenger is by far the most mature and moving film made yet about the Iraqi invasion, even if Iraqis themselves don’t make an appearance as figures mentioned in battle stories. It’s a telling, ethically vibrant film, a home-front war movie with a difference – it’s about the task of manning the home-front, by reporting the dead to their families. We think Ben Foster‘s new reassignee is merely a buttoned-down battle case, and like him, the film is realigning the war-movie priorities – there’s combat, but then there’s the result, families with holes in them, keening parents, shattered wives, orphaned children. Woody Harrelson, as the commanding officer in a pas de deux, also seems to be a stereotype that sheds onion layers – by the middle of the film, after harrowing house visit after house visit, the two men are as complicated by rage and secrets and shame and vulnerability as any that an American independent film has produced in years. The story follows their tentative bonding, and Montgomery’s impulsive attraction to a young widow (the amazing Samantha Morton) after she reacts very differently to the soldiers’ news than they expect her to. But the achievement is more on the micro-level: the time spent absorbing wholesale grief (Moverman’s camera is always ready to hang back and give the victims air, while Foster’s hardass always wells up with tears but freezes), the conversations full of unspoken intention, the rhythms of scenes as the characters, responding to disaster, hunt internally for ways to react. And the acting is razor-sharp, down to Steve Buscemi as a soldier’s father, upping the film’s ante in his pivotal scene, and then raising it again later, unexpectedly. Overall, there’s a sense of tender responsibility here that feels like a tall glass of ice water in an arid modern movie culture most often overrun with simplism (that’s a real word, and a good one) and idiot noise.

The Thin Red Line (1998)

The year’s true World War II masterpiece, The Thin Red Line, Terrence Malick’s comeback film (after a twenty-year hiatus from filmmaking) takes place during and around the battle of Guadalcanal, but is in reality far more concentrated on the emotional experience of battle and the impact, poetically invoked here, of human warfare upon individuals and upon nature. Essentially a three-hour, nonnarrative experiment, there are no main characters—just an ensemble of thirty or more figures—and there’s no story—just impressions, experiences, feelings (the complex weft of narrative voices often do not synch up with on-screen personas), and astonishing images. Oh, yeah—it’s based on James Jones’s 1962 novel, though you’d never know it. Lots of stars packed in: Sean Penn, Nick Nolte, George Clooney, Jim Caviezel, John Cusack, Woody Harrelson, John Travolta, Jared Leto, and Miranda Otto.

Related articles

Saving Private Ryan (1998)

The first and more orthodox World War II war film of 1998, Steven Spielberg’s heroic yarn Saving Private Ryan follows a troop of assorted all-American types through the European theater on what seems to them to be a fool’s mission: retrieving a soldier (Matt Damon) from battle after his brothers are killed elsewhere. Tom Hanks rings true as an unlikely macho commander, and the opening D-Day sequence is justly famous for being gut-twisting. With Edward Burns and Tom Sizemore.

Related articles

A Midnight Clear (1992)

It’s Christmas, 1944; the Germans have nearly lost, and everyone knows it. Six mostly inexperienced soldiers (including Ethan Hawke, Frank Whaley, Will Wheaton, and Gary Sinise) are selected for special assignment because of their high IQs, so we know we’re in for a thoughtful movie—no “kill the Kraut” heroism here. After stumbling through the darkened, snowy forest they hole up in an abandoned mansion, wondering what to do; the Germans they meet feel likewise, and for a while—but not forever—it seems they won’t exchange fire more dangerous than snowballs. A Midnight Clear, an unjustly overlooked film, is based on a William Wharton novel.

Related articles

Paths of Glory (1957)

Stanley Kubrick’s bare-knuckle screed about war and military injustice, set during World War I and amid the French; Kirk Douglas plays a colonel ordered to shove his men into a hopeless slaughter; when they eventually refuse, he’s compelled to court-martial a handful of random infantrymen for cowardice. Paths of Glory is muscular storytelling and unremitting moral outrage.

Related articles

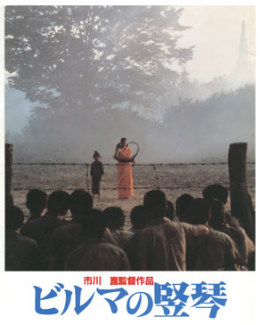

The Burmese Harp (1956)

The Burmese Harp is a haymaker of an antiwar film from Japanese moviemaker Kon Ichikawa, in which a soldier escapes death in Burma by masquerading as a Buddhist priest, then finds himself transformed by the horrors of war into a holy man dedicated to burying the countless dead.